Analysis: Beyond the archlights, Cannes’ murky political play over Iranian cinema

By Fateme Torkashvand

While the Cannes Film Festival, held earlier this week, has reinvigorated the narrative against the Islamic Republic of Iran by awarding its top prize to Jafar Panahi, public opinion, both globally and within Iran, is increasingly wrestling with a range of complex questions.

Why is a film festival engaging in political actions? How can accusations of authoritarianism be reconciled with the open participation of both underground and official Iranian filmmakers at Cannes?

The approach of Cannes Film Festival organizers toward Iranian cinema warrants closer scrutiny, especially as their stance is now widely regarded as political by critics across the ideological spectrum.

“Classically, and in Carl Schmitt’s terms, the political concerns the distinction between friend and enemy. Later thinkers expanded on this, but in everyday usage, ‘the political’ is often confused or conflated with ‘politicization’,” Amir Reza Mafi, author and professor of philosophy and media, told the Press TV website.

Mafi explained that the political, in its ontological sense, draws boundaries between self and enemy, and morally between good and evil.

In this sense, the political is always present and essential. In contrast, politicization is a vulgarized and simplistic phenomenon, arising when a particular domain becomes subject to political forces and electoral competition.

Mafi emphasized that, from this perspective, two criticisms apply to Cannes’ actions: first, that it constitutes a hostile act against Iran; and second, that cinematic merit does not seem to be the primary basis of judgment.

Thus, Cannes’ behavior, following the French government’s adversarial posture toward Iran, represents a political act based on the friend-enemy dichotomy.

Meanwhile, the Iranian filmmaker, who presents a version of politics based on his own warped worldview, embedded in politicized concerns through film, becomes a tool for advancing the aims of the enemies of the country he originally belongs to.

This is especially problematic given that the central themes of his film, such as revenge against an interrogator, are not part of the core, high-priority concerns faced by ordinary Iranians.

A departure from cinematic values

Prominent film critic Saeed Mostaghasi, speaking to the Press TV website, noted that political cinema is a “valid genre,” referring to legendary filmmakers such as Costa-Gavras and Angelopoulos who dabbled with political themes in their films.

He distinguishes ideological films – those functioning like weapons in political battles – as ones that may be awarded regardless of their cinematic merit.

When Panahi was banned from filmmaking in Iran, Mostaghasi noted, Thierry Frémaux, the artistic director of Cannes, declared that the Iranian filmmaker would always have a place at the festival, symbolized by a chair reserved in his name.

“This shows that for Cannes, Panahi's mere presence matters more than what film he makes –a practice unheard of for any major filmmaker in cinema history,” he said.

Iranian public opinion matters little to Cannes

In a remark that stirred controversy, French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot took to X (formerly Twitter) after Panahi’s Palme d’Or win to admit to the political undercurrents influencing international festivals like Cannes, especially against the Islamic Republic.

“In a gesture of resistance against Iranian repression, Jafar Panahi has won the Palme d’Or—an honor that rekindles hope for freedom fighters around the world,” he wrote.

But do Cannes organizers not realize the impact such a political gesture might have on Iranian public opinion? Or are their political objectives so dominant that they’re willing to overlook the interests of the Iranian people?

While Cannes awards its Palme d’Or in the name of freedom, serious questions in Iran, especially among film industry circles, are intensifying about how a film was produced underground and how its production team left the country.

Cinematic values go to toss

Veteran film critic Khosro Dehghan described the event as perplexing and ambiguous.

“I just don’t understand what’s going on. Filmmakers like John Ford and Hitchcock didn’t engage in these theatrics; they made their films and moved on, like Hafez and Saadi did with their poetry. Whether to call this good or bad is hard to say—it’s just confusing.”

Ham-Mihan newspaper dismissed the claim that Cannes’ award was apolitical as “naive,” describing Panahi as a politically active figure tied to the events of 2009, whose realistic cinematic style has since taken a political, or, as some say, overly politicized turn.

Renowned filmmaker Farzad Motamen recalled on Instagram that in 1975, Cannes awarded the Palme d’Or to Algerian director Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina in recognition of Algeria’s independence.

“Cinematic values didn’t play a role in that decision,” he said. Years later, Gilles Jacob, when interviewed, didn’t even remember Hamina’s name, asking his colleague: ‘What was the name of that Arab we gave the prize to?’ That Arab!”

Some film journalists argue that constructing a heroic narrative around an Iranian filmmaker, despite logistical implausibility, serves as a media project for Cannes.

Others point to the official participation of another Iranian filmmaker, Saeed Roustaee, and his team as evidence that Iran’s film community continues to engage openly with Cannes.

They suggest that critical remarks by some directors, under pressure from Western media, are merely one of many tools used to shape anti-Iranian narratives.

This perspective is seen as a natural reaction to Cannes’ politicized conduct, which appears to lack genuine artistic engagement with the film in question.

Even some elements opposed to the Islamic Republic acknowledge the political nature of Panahi’s award.

Awards fade, films remain

Iranian film critics argue that, in the end, political buzz fades, but the film itself endures—the work of the artists remains.

“A politicized or ideological film, aimed solely at opposing or defending a political structure, will fail to endure. But a political film that clearly delineates good and evil, and arises from the real problems of its society, will have a lasting impact,” said Mafi.

Mostaghasi echoed this sentiment, noting that a year from now, just as no one remembers what awards Chaplin, Hitchcock, or Ford won, people will still be watching and learning from their films.

“Awards and the controversies around them are forgotten—what endures are the films’ internal values,” he stated.

Attack against the resistance amid genocide

France’s political use of the Cannes Film Festival extends beyond cultural influence.

Amid the ongoing Israeli genocidal war on Gaza, an issue that transcends politics and constitutes a grave humanitarian crisis, Cannes redirected global attention by awarding its top prize to an Iranian filmmaker.

In doing so, it effectively co-opted the term “resistance,” a concept rooted in over 70 years of Palestinian defiance against Israeli occupation and apartheid, resistance that has been openly supported by the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The term is now being reframed through a Western media lens to center Iran, rather than the Palestinian struggle.

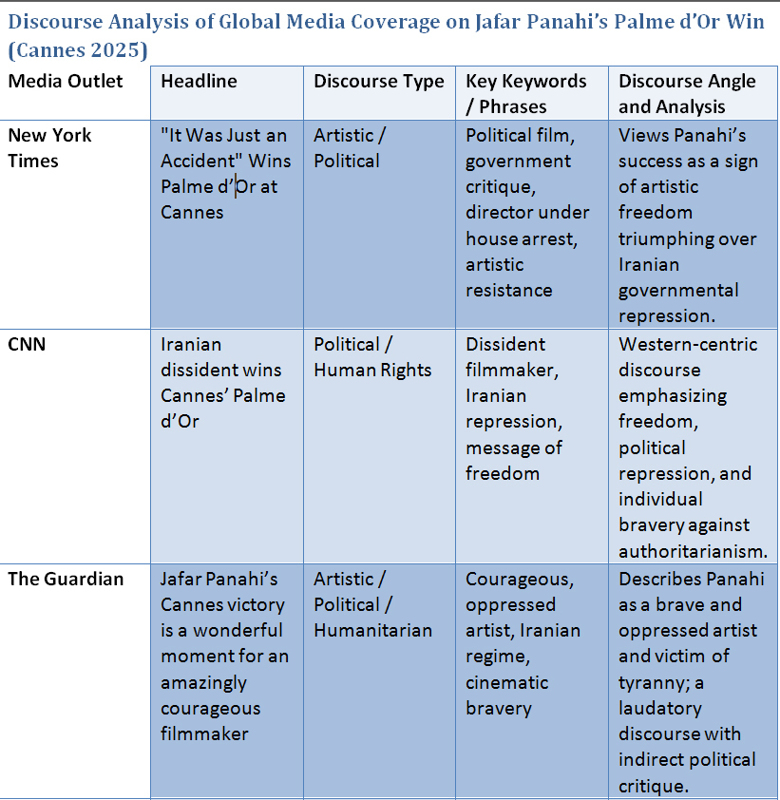

A quick survey of mainstream headlines and reports reveals a consistent bias against Iran, framed under the guise of a film award.

It is worth examining ten notable examples of such coverage.

Fateme Torkashvand is a Tehran-based journalist specializing in cultural affairs.

Five ‘elite’ Israeli forces killed in Khan Yunis ambush by Gaza fighters

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Iran issues warning as Europeans 'ponder another major strategic mistake'

Israel threatens to intensify Lebanon strikes if Hezbollah not disarmed

Iran: Israel carrying out strikes on Lebanon with US green light

Iran’s Pezeshkian, Egypt’s Sisi say keen to enhance bilateral ties

Yemen launches hypersonic strike on Israel’s Ben Gurion

Europe doubles arms imports from Israel amid growing boycott calls

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website